My first go at writing an application in Rust has been slightly frustrating. Coming in from using mostly dynamic languages every day I quickly found myself butting heads with Rust’s borrow checker. However, I’ve found that this is a fair price to pay for a statically typed language with a focus on memory safety and performance.

While these Rust features do increase the barrier of entry for newcomers such as myself, they also help to keep your code in check and are certainly major contributing factors to the language’s success.

Another interesting point is that Rust doesn’t have a GC (garbage collector). As soon as something in your code is not required anymore (a function call returns) the memory associated with that scope is cleaned up. Rust inserts Drop::drop calls at compile time to do this. I imagine this is similar in concept to the way that IL or code weaving is done in the .NET world. This fact means that Rust doesn’t suffer from performance hits that languages with a GC tend to sometimes encounter. Discord wrote an interesting article on how they improved performance by switching from Go to Rust that touches on this particular point.

Goals

To take a look at the Rust language and ecosystem at a really high-level, I decided to write a simple tool. My goals were to:

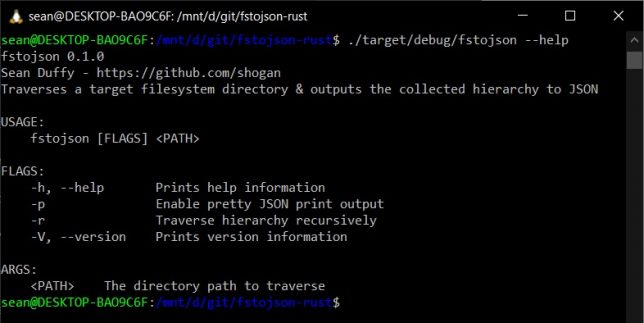

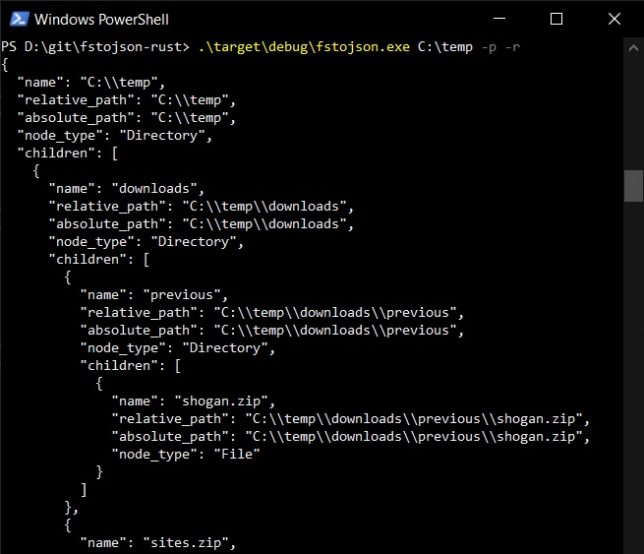

- Write a CLI tool, small in scope. The tool will traverse a target directory in the file system recursively and print the structure to stdout as JSON.

- Get a feeling for the language’s syntax.

- See how package management and dependencies work.

- Look at what the options are for cross-compiling to other platforms.

The tool – fstojson

Here is the small tool I wrote to achieve the above list of goals: fstojson-rust.

I’ve compiled my first app on macOS, Linux and Windows all from the same source, with no issues whatsoever.

Rust Packages

On my first look at Rust, packages were simple to understand and use. Rust uses “crates” and they work very similarly to JavaScript packages.

To add a crate to your project you simply add the dependency to your Cargo.toml file (akin to a package.json file in Node.js).

For example:

[dependencies] serde_json = "1.0.68"

Once crates are installed with the cargo command, you’ll even get a lock file (Cargo.lock), just like with npm or yarn in a Node.js project.

Rust cross compiling

The first time you install Rust with rustup, the standard library for your current platform is installed. If you want to corss compile to other platforms you need to add those target platforms seperately.

Use the rustup target add command to add other platform targets. Use rustup target list to show all possible targets.

To cross-compile you’ll often also need to install a linker. For example if you were trying to compile for x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu on Windows you would need the cc linker.

Thoughts and impressions

To get a really simple “hello-world” application up and running in Rust was trivial. The cargo command makes things really easy for you to scaffold out a project.

However, I honestly struggled with anything more complex for a couple of hours after that. Mostly fighting the “borrow checker”. This is my fault because I didn’t really spend much time getting acquainted with the language initially via the documentation. I dove right in with trying to write a small app.

The last time I wrote something in a System programming language was at least 7 or 8 years ago – I wrote a tool in C++ to quiesce the file system in preparation for snapshots to be taken. Aside from that, the last time I really had to concern myself with memory management was with Objective-C (iOS), before ARC was introduced (See my first serious attempt at creating an iOS game, Cosmosis).

In my opinion, some of Rust’s great benefits also mean it has a high barrier of entry. It has a really strong emphasis on memory safety. I came at my first application trying to do all the things I can easily do in Typescript / Javascript or C#.

I very quickly realised how different things are in the Rust world, and how this opinionated approach helps to keep your code bug-free and your apps safe on memory.

Closing thoughts

After years of dynamic language use, my first introduction to Rust has been a little bit shaky. It’s a high barrier of entry, but with that said, I did find it satisfying that if there were no compiler warnings my code was pretty much guaranteed to run without issue.

The Rust ecosystem is active and thriving from what I can tell. You can use crates.io to search online for packages. You can use rustup to install toolchains and targets.

There are tons of stackoverflow questions and answers and the documentation page for Rust is full of good information.

Going forward I’ll try to dig into the Rust language a bit more. I’m on a little bit of a journey to try different programming languages (I’ve had a fair bit of experience in C# and Typescript / JavaScript, so I’m branching out from those now).

I discovered this post recently – A half-hour to learn Rust. In hindsight it would have been great to have found that before diving in.

Update: thanks to noah04 on GitHub for their improvements PR on applying some Rust idioms.